In part 1 of this blog, I explained training periodization, and talked about the first two macrocycles: off-season and pre-season. Now I’ll talk about the remaining macrocycles: in-season and post-season.

In-Season

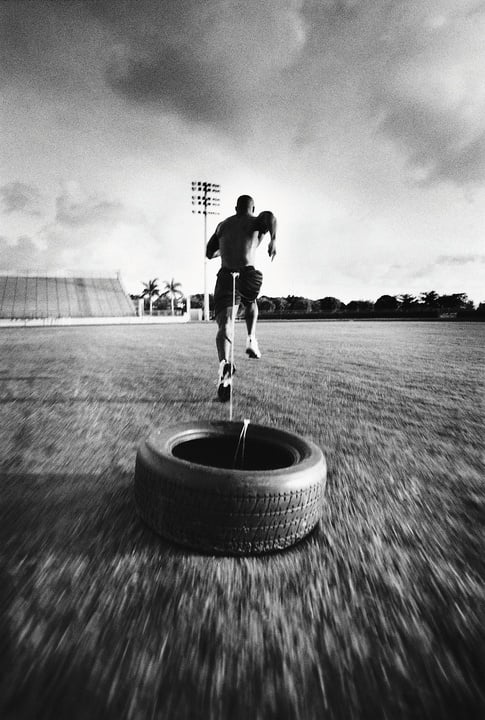

Once the competitive season begins, scheduling time to get in to lift is a lot more difficult due to the practices, games, and travel that are happening. To me, in-season lifting is sometimes undervalued in the competitive/athletic world because of the fact that the primary focus is to win games or matches, not lift weights. However, I believe that this is one of the most important (if not the most important) times during the year because of what lifting can do for the athlete throughout the competitive season and into the off-season.

Once the competitive season begins, scheduling time to get in to lift is a lot more difficult due to the practices, games, and travel that are happening. To me, in-season lifting is sometimes undervalued in the competitive/athletic world because of the fact that the primary focus is to win games or matches, not lift weights. However, I believe that this is one of the most important (if not the most important) times during the year because of what lifting can do for the athlete throughout the competitive season and into the off-season.

The goal of in-season lifting is simple: maintain what you have built in the off/pre-season and make sure that no muscular imbalances develop. This is not a time to try and increase your squat or bench by 50 pounds. It is a time to make sure that your body stays healthy and you are able to preserve the muscle, strength, and power that you have built throughout your season. Doing this will not only keep you healthier for your sport, but will also set you up for better long-term development during the subsequent off-season. Think about it: If you lose the vast majority of strength, power, and muscle mass you’ve built over the in-season, you are basically starting at square one when the season is over. If you are able to preserve 85% of that strength and power, you are starting further along than you were the year before, which allows you to make bigger gains.

Recommendation:

Training Frequency: 2 days per week

Mode: Medium Sport Specificity

Volume: Low

Post-Season

When your competitive season comes to a close, there should be some time to relax and recover from it. Take time and reflect on how you performed and what you could have done to be better in different aspects of your activity. Start creating a plan on how to improve those things once your training ramps up again.

As for training during this period, it should still happen. Your body is still recovering, but you want to make sure you do not totally fall off the map by not doing any type of exercise or physical activity. This is a perfect time to play or participate in some other sports or change up your weightlifting routine. You basically have free reign on your choices under one circumstance: get away from your actual sport/complete lifting routine.

This macrocycle does not last long, but it is an important one. You have been competing for months and want to avoid being burnt out on the sport you love, so getting away will be good. Do something different; just be active. After 3 to 4 weeks of light activity, you can begin your off-season program and start the quest to better yourself for the next competitive season.

Recommendation:

Training Frequency: 2 to 4 days per week (light activity)

Mode: Low Sport Specificity

Volume: Low-Medium

***

Overall, there is no exact science that is going to work perfectly every time when you are building your own training programs. You will always need to make tweaks, even to the best programs around. This blog provides the framework for developing a solid program, but the devil is in the details. You want to make sure that you have everything planned out as you progress through the competitive season. Some things may not go as planned, but that is okay. The ultimate goal is to make you the best athlete you can be in the sport or activity you are doing!

When putting together a program for anyone, client or athlete, you always want to have an idea when you would like to peak, or be at your best throughout that calendar year. For

When putting together a program for anyone, client or athlete, you always want to have an idea when you would like to peak, or be at your best throughout that calendar year. For  Most of us might have been lucky to get out and play a handful of times over the winter, but some might be picking up a club for the first time in almost five months or more when that first tee time rolls around. Regardless of how many times you have played in recent months, everyone can benefit from improving golf-specific fitness areas before the full-fledged season begins.

Most of us might have been lucky to get out and play a handful of times over the winter, but some might be picking up a club for the first time in almost five months or more when that first tee time rolls around. Regardless of how many times you have played in recent months, everyone can benefit from improving golf-specific fitness areas before the full-fledged season begins.

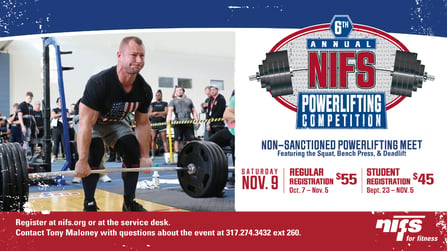

Whether you have particpated in our Powerlifting Competition or interested in joining, I’m going to give you a solid progression that will allow you to develop a strong power clean with proper technique. The following movements can be a starting point for beginners or experienced lifters looking to get a fresh perspective on their current programs.

Whether you have particpated in our Powerlifting Competition or interested in joining, I’m going to give you a solid progression that will allow you to develop a strong power clean with proper technique. The following movements can be a starting point for beginners or experienced lifters looking to get a fresh perspective on their current programs.

In NFL and college football, each week, a star player is hit with a sidelining injury. Possibly lost for multiple weeks, months, or at worst, the whole season. Injuries that are usually the result of bad luck or not being as physically prepared as they could have been. Hopefully your team, **knock on wood**, does not or will not have to deal with this at any point during their season. My team, my beloved

In NFL and college football, each week, a star player is hit with a sidelining injury. Possibly lost for multiple weeks, months, or at worst, the whole season. Injuries that are usually the result of bad luck or not being as physically prepared as they could have been. Hopefully your team, **knock on wood**, does not or will not have to deal with this at any point during their season. My team, my beloved  As you can see, progression of strength (and power with other lifts) has to be maintained year round. This goes for all athletes throughout their seasons. If they want to continue to improve, they must prevent the loss. It is as important of a cycle of training as any. Without a properly structured in-season maintenance phase, you will be starting from the same place every time you start a new offseason training program.

As you can see, progression of strength (and power with other lifts) has to be maintained year round. This goes for all athletes throughout their seasons. If they want to continue to improve, they must prevent the loss. It is as important of a cycle of training as any. Without a properly structured in-season maintenance phase, you will be starting from the same place every time you start a new offseason training program. You have finally achieved your goal of adding some lean muscle mass, so what now? Where do you go next? The next step I would take would be to train your body to use those newly developed muscles to their fullest potential. This increase in strength building can come from numerous sources, some of which you may have already experienced.

You have finally achieved your goal of adding some lean muscle mass, so what now? Where do you go next? The next step I would take would be to train your body to use those newly developed muscles to their fullest potential. This increase in strength building can come from numerous sources, some of which you may have already experienced.  Okay, so you’ve been successful in your first two phases of developing your new workout program. You have progressed in your

Okay, so you’ve been successful in your first two phases of developing your new workout program. You have progressed in your  Once you have mastered

Once you have mastered  Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither is a physically fit and healthy body. The great city was built as the result of the culmination of years and years of hard work. From streets to buildings, each single brick or stone was set with a vision in mind to create the best city in the world. I’m sure many mistakes were made throughout the process; however, those mistakes were only microscopic setbacks in the overall plan.

Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither is a physically fit and healthy body. The great city was built as the result of the culmination of years and years of hard work. From streets to buildings, each single brick or stone was set with a vision in mind to create the best city in the world. I’m sure many mistakes were made throughout the process; however, those mistakes were only microscopic setbacks in the overall plan.